Introduction

Curators: Isabel Dzierson (Dresden), Marianne Rigaud-Roy (Lyon), Sandra Sunier (Geneva)

Exhibition Design: Holzer Kobler Architekturen (Zurich / Berlin)

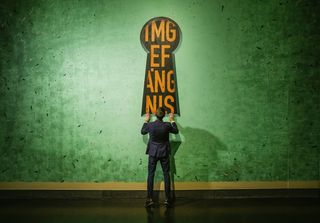

Life behind bars eludes our gaze and, to a large extent, our awareness. Prison becomes a place that evokes a mix of unease and fascination while revealing so much about our communal way of life and our fundamental human need for punishment and retribution. What role does prison play today in our social coexistence? Does it stand for justice? Redemption? Or for prevention and protection? And how does one counter the contradiction that the promise of rehabilitation often goes unfulfilled?The exhibition invites visitors to take a closer look at these questions, but also to get a better insight into everyday life in prison. Various protagonists are given the opportunity to have a say about their roles and express their views. Historical, philosophical, anthropological and sociological analyses are showcased alongside various objects fashioned by the prisoners themselves, photographic documents, and works from the field of art, music and literature. The result is a joint project that is transnational in many aspects, one in which the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, the Musée des Confluences in Lyon, and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum in Geneva have each participated in equal measure.

The Exhibiton Rooms

I. Prison

In Europe, imprisonment became a form of lawful punishment immediately after the French Revolution. It was meant to do away with the previous deterrent, namely corporal punishment. Imprisonment was seen as a more humane way of dealing with criminals. Detention also allowed literacy training programmes and work education, and the observance of rules aimed at facilitating reintegration into society.

But even those who were among the first to advocate prison sentences were keen to point out their potential drawbacks, namely that marginalisation through imprisonment could jeopardise a person’s reintegration into society. They also felt there was a genuine risk that life among a community of offenders could help establish an ‘academy of crime’. All of which highlights the paradoxical nature of prison sentences.

II. Held Prisoner

As they start their prison sentence, inmates surrender their identity and independence as civilians. From then on their lives are defined by prison structures and a stringent daily routine. The keys are literally in the hands of prison officers, who have the monopoly on any use of force as legitimised by the state, but also a duty of care. In prison, the prime concern is security, with social interaction shaped by prohibitions and taboos. This in turn often creates additional psychological and physical stress, over and above the actual punishment or the everyday strains of a difficult job. And yet, even within this power structure, all the parties involved defy the rules and regulations time and again.

III. The human factor

Time in a prison cell seems to drag on forever. Prisoners’ daily routines are defined by repetition, waiting, and loneliness. Their stress is compounded by confined cells, constant background clamour, and unpleasant odours. In such confined surroundings, prisoners adopt different methods to try and escape the tedium and feel alive, and create some breathing space for themselves. Their work routines, the way they arrange their cells, communicate with outsiders or discipline their bodies helps to cope more effectively with the fact that they are deprived of their personal liberty.

IV. ‘No!’ means ‘no!’

Time and again prisoners rebel, whether it’s by possessing objects banned in prison, using graffiti tags, or through revolts, arson or suicide attempts. Prisoners try and thwart their captive state through acts of individual or collective disobedience, by damaging prison property, or through protests that can sometimes prove fatal. For them it is a way of warding off the feeling that they are being devoured by the prison machinery. After all, to resist is to exist. Battles such as these contribute to the atmosphere of constant tension – even among those inmates who do not question the penal system as an institution.

What are the alternatives?

Many societies today regard imprisonment as the most effective form of punishment because it coincides with our urgent need for protection and security. The prison assumes the role we expect of it, namely to isolate and supervise offenders and criminals. And yet, captivity has serious implications for the individual. In some traditional communities for example any deprivation of liberty through forcible confinement is unthinkable. There the aim of punishment is to get the individual to make amends and ensure their reintegration into society.

So does that mean that prisons are the only answer? Legislation that provides for alternatives does exist. If given greater consideration, it could represent different, more positive options than the prison system itself.

Our Partners

musée des Confluences, Lyon (MDC)

In Lyon, where the Rhône and Saône rivers meet, the knowledge of centuries and continents also flows together in an imposing glass building: In addition to the earth, its origins and geography, the musée des Confluences focuses above all on humanity. The museum's permanent exhibitions are dedicated to the questions "Where do we come from? "Who are we?" and "What do we do?". The exhibition "In Prison" (Prison, au-delà des murs) was on display here until June 2020.

International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum, Geneva (MICR)

Emotions, discoveries, food for thought: The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum offers fascinating insights into humanitarian work in its permanent exhibition. In its special exhibitions, the museum, which is dedicated to the work of the Red Cross founder Henry Dunant, constantly addresses current social issues. The exhibition "In Prison" celebrated its premiere here in 2019. Until 31 January 2021, the participatory exhibition project "COVID-19 and Us. By Magnum Photos and you" can be seen here until 31 January 2021.