About the exhibition

Invitation to hold your breath and take a deep breath

Air is omnipresent and yet elusive. It is always in motion and connects living beings - across ecosystems and geological eras. We humans also live in and through the air: we breathe it in and out around 20,000 times a day. And yet we behave as if we are not dependent on it. Through our actions, we change the air and thus increasingly also our living conditions.

The exhibition takes these changes as an opportunity to examine not only the physical properties of air but also its social impact - both locally and globally. Follow the movements of air through different ecosystems and geological eras and across national borders.

At the beginning of the exhibition tour, an air archive brings together personal air and perceptions of air. Fog catchers, which are used to filter water out of the air in places with low precipitation, capture air movements and air phenomena for visitors in the exhibition. A giant air conditioning pipe tells of the attempts to bring the air under control.

Numerous works of art and interactive stations are integrated into the exhibition, inviting visitors to discuss global environmental issues related to the state of the air. With an “emissions memory”, for example, the often abstract dimensions of CO2 emissions can be revealed.

Gallery

The exhibition rooms

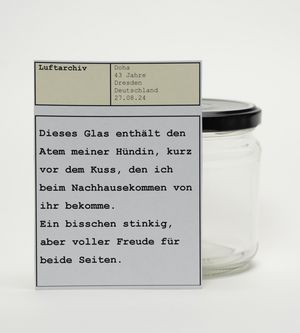

Air archive

200 stories in a jar

We share it with each other and yet we do not breathe the same air: what at first glance appears to be a collection of empty vessels is actually an archive of the most diverse airs and individual perceptions of air. Although the contents of the jars almost always look the same, the samples are very different from one another: each one tells the story of how air relates people to their environment in the most diverse ways and becomes a carrier of human sensations.

McLean's monthly sheet of caricatures, Public Domain, National Library of Medicine

Invisible

Air as a connection

How do you grasp something that cannot be grasped? Air is a mystery to people. It is invisible, formless and fleeting. What is in the air? How can its movements be understood and who does it connect? How we answer these questions varies historically and culturally: they range from sensory perception and scientific observation to mythical tales and religious interpretations. How do these ideas shape our relationship to the air and our interaction with it?

© Dyson

Measured

Air under control

Air never stands still. We are exposed to the incessant changes in its temperature, composition and movement. And dream of being able to control the air. Today, it is scientifically measured, politically regulated and technically designed. From “smoke-free” cities to experiments designed to make people completely independent of the earth's atmosphere: Who do regulated air zones and artificially created climates include and who do they exclude? Who decides what is good and what is bad air? And how does air, which is invisible, transboundary and always in motion, resist these attempts at control?

The Atmospheric Data Collective (ADC), 2022, Tom Corby

Debatable

Air as a common good

Like the high seas or the Antarctic, the Earth's atmosphere is not under the control of any government: It is considered a global commons. This makes it difficult to negotiate binding rules for its protection and use. Is there a right to clean air? How are the needs of all breathing creatures taken into account? What opportunities and risks lie in technical solutions such as geoengineering?

Artistic works (selection)

Project participants

Project team

Neli Wagner (DHMD), curator and project manager

Nele-Hendrikje Lehmann (DHMD), co-curator and research assistant

Laura Schmidt (DHMD), curatorial assistant, mediation

Bettina Beer (DHMD), project assistant

Exhibition design

Janek Müller (Berlin), dramaturgy & scenography

Wir von Kebnekaise - Tina Buß, Irmhild Gumm (Berlin), design planning, execution planning and production management

Wir von Kebnekaise with Matthies, Weber and Schnegg (Berlin), graphic design

Artistic works by, among others:

The Atmospheric Data Collective (ADC), Frank Bloem, Anna and Bernhard Blume, Zlatko Ćosić, Vibha Galhotra, Sonja Hornung and Daniele Tognozzi, Emily Parsons-Lord, Werner Reiterer, Karolina Sobecka and Chris Woebken, Koki Tanaka, Rikuo Ueda, Nils Völker and many more.

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Keyvisual

Funkelbach, graphic design